The Cause | The Types of the Annular Tear | Healing | Last updated: 9/25/16

As we have learned from the "Anatomy Page," the disc is made up of two parts: a Jell-O-like center called the nucleus pulposus (nucleus) and a tire-tread-like periphery called the annulus fibrosis (annulus) (see figure #1).

As we have learned from the "Anatomy Page," the disc is made up of two parts: a Jell-O-like center called the nucleus pulposus (nucleus) and a tire-tread-like periphery called the annulus fibrosis (annulus) (see figure #1).

Normally, the nucleus is held (or corralled) firmly in place by the tougher annulus fibrosus. Under this ideal situation, the biomechanics of the motion segment (a motion segment is a disc, which is sandwiched inbetween two vertebrae) are such that the nucleus will bear the majority (~80%) of the tremendous downward weight of the body (the axial load), which spares the pain-sensitive posterior annulus from the majority of this stress.

The facet joints also carry about 20% of the axial load.

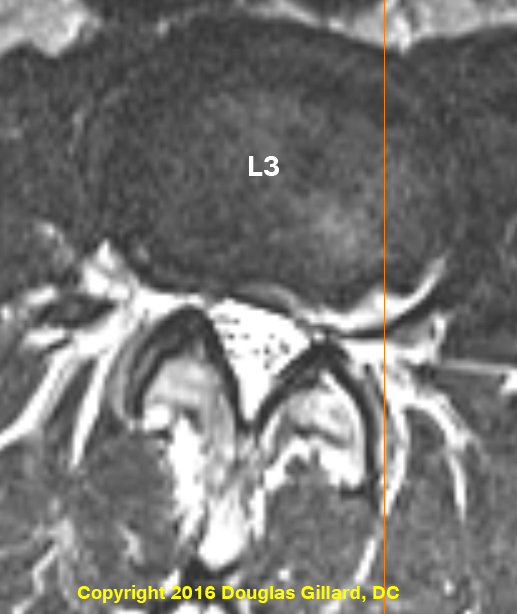

The picture to the left demonstrates a massive concentric annular tear which is superimposed upon a broad-based disc herniation. This client had severe low back pain with pain radiating from the low back, on to the top of the left thigh. It is located from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock and is bright white (radial opaque or hyperintense) in color, secondary to a wicked inflammation process.. Can't see it? Then click here.

As we age, the ability of the annulus to contain the pressurized nucleus will become compromised secondary to a drying and weakening phenomenon (called degenerative disc disease) that occurs in all discs (especially in the 40s). As a result, the nucleus may rip its way through the annulus and cause an annular tear. The annular tear not only changes the axial load biomechanics of the disc (now the weight shifts posteriorly onto the pain-carrying nociceptive fiber of the sinuvertebral nerves and overloadsthe facet joints), but also releases evil biochemicals called cytokines [especially tumor necrosis factor alpha] into the now-exposed sinuvertebral nerves endings. Bottom line, severe low back pain can result in some patients (but, confusingly, not all patients). This type pain is called "discogenic pain."

AKA: note to the grammar police: in Europe, annulus is spelled anulus.

The annulus of the disc is made of crisscrossing sheets of collagen called lamellae (like a tire tread kind of), which are normally tremendously strong and pliable. In fact biomechanical compression studies have demonstrated that the vertebrae themselves will fracture under experimentally induced loads before the annulus succumbs. With normal age, however,the annulus tends to lose strength and pliability which makes it more susceptible to the development of annular tears.

In some patients, this degenerative process can be greatly accelerated by lifestyles that involve heavy labor or are extraordinarily sedentary. Genetics is also known to play a significant factor in pathological disc degeneration. For example, some patients may have genes that give rise to inferior types of disc-building-materials ( i.e., proteoglycans and/or different types of collagen and even elastic tissue).

Although there are different "flavors" of annular tears, radial annular tears are the most common and begin within the inner annulus (adjacent to the nucleus) and then work their way toward the pain-sensitive periphery of the annulus, which (as noted above in the figure one legend) is filled with pain-carrying nerve fiber called the sinuvertebral nerves.

The Latest research (2012) dictates that the actual discogenic pain that a patient feels may result from a combination of two things: (1) evil biochemicals called cytokines, which are spawned from the degenerated disc itself (especially the nucleus pulposus) which, because of the passageway created by the annular tear, come in contact with the nociceptive (pain producing) nerve endings in the outer annulus and initiate a painful inflammatory process; and (2) biomechanical changes which have resulted secondary to the new passageway communicating the nucleus with the outer annulus (i.e., the annular tear) which causes a loss of hydraulic pressure within the nucleus and redistributes loadbearing from the center of the nucleus on to the posterior annulus (which is exactly where we don't want the axial load to be, because this is where all the pain fiber is). Now, mechanical compression of the already inflamed sinuvertebral nerves may cause severe discogenic pain. In other words, the pain is because the sinuvertebral nerves within the posterior annulus have become "activated" with inflammation (which may cause pain in and of itself) and compressed by the weight of the body because the biomechanics of the disc have been changed by the annular tear from the center of the disc to the posterior periphery.

* The other thing that is important to understand is that some patients can have annular tears (especially construction workers or similarly arduous  employments) without having any pain at all. It is still not completely understood why some patients suffer horrible pain with annular tears and others don't. It probably has something to do with individual sensitivity to the cytokines and/or the patient's own immune response to the chemical exposure upon the sinuvertebral nerves.

employments) without having any pain at all. It is still not completely understood why some patients suffer horrible pain with annular tears and others don't. It probably has something to do with individual sensitivity to the cytokines and/or the patient's own immune response to the chemical exposure upon the sinuvertebral nerves.

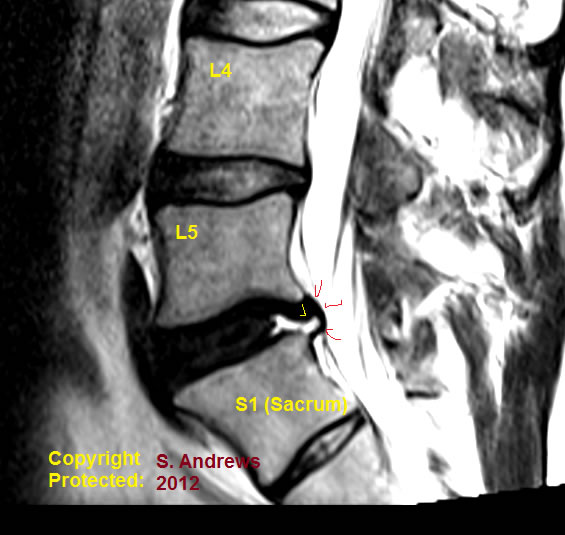

The picture left (T2 sagittal) demonstrates a massive annular tear (yellow arrow points to white horizontal line which is the annular tear) within the posterior L5 disc. The annular tear is superimposed upon a small disc protrusion (red arrows).

It is not common to visualize such a tear without gadolinium enhancement, for they are typically invisible and MRI.

Furthermore, it is very uncommon to see a tear this large!

Note that the L5 disc is severely desiccated (black when it should be much lighter in color, like the ones above); however, the disc height is still maintained which equates to only mild degenerative disc disease.

The client also had a rudimentary disc between S1 and S2, which occurs in less than 10% of humans, but is not believed to be a pain generator.

Radial Tears | Rim Lesions | Concentric Tears | HIZ Sign

There

are three main types of annular tears (aka: annular fissures) that occur in the human disc:

The

rim lesion, which

is a horizontal tearing of the very outer annular fibers of the disc near their

attachments into the ring apophysis (i.e. the Sharpey's Fibers); the concentric

tear, which is a splitting apart of the lamellae of

the annulus in a circumferential direction; and the radial

tear, (aka: full thickness annular tear) which is a horizontally orientated annular tear that courses from the inner nucleus pulposus to the very outer region of the disc (see figure #2). Such tears May allow the pressurized nucleus pulposus to squirt through the tear, out the back of the disc and into the epidural space, which in turn may compress the adjacent nerve roots--such a condition is called a disc herniation.

I have created a webpage for each one of these tears which can be further explored by simply clicking on the above links.

Like most other injuries, the body will attempt to heal the annular tear by filling in the gap with scar tissue. depending on the amount of degeneration within the disc, anecdotally, healing times can be 18 months or even more. New blood vessels will grow from the periphery of the disc down toward the nucleus through the annular tear (it is these blood vessels in part that supplied the building blocks needed for the scar tissue to form). Unfortunately, pain-carrying new nerve fiber acompany the blood vessels down into the center of the disc! This is not a good thing, because now has a higher capacity to generate pain because it has more pain-carrying nerve fiber within it. This phenomenon, as well as a similar phenomenon which may occur vertebral endplate, is most likely the reason why patients with annular tears often suffer bouts of pain throughout their lives..

The only way to know for sure whether or not a disc has suffered an annular tear is by a test called discography. Basically it is a procedure where a specialist injects dye (contrast) into this nucleus pulposus (center) of the disc and then pressurizes the disc in order to see if this pressurization re-creates the patient's usual and customary pain. If it does, the disc is said to be concordantly positive (i.e. that disc is generating "discogenic pain"). In order to further validate this finding, lidocaine (a powerful anesthetic) may be injected into the disc to see if the pain will now disappear--the theory being that the lidocaine numbs the inflamed sinuvertebral nerves, which in turn takes away the pain. Then, the disc above or below (assuming it is not a suspect for annular tear) is tested in the same manner in hopes of finding that disc to be non-painful (i.e., a control disc). While all this is happening, the patient is blinded to what is going on (i.e., the doctor does not tell the patient which disc he's injecting and what to expect).

Ideally, a CT scan should be performed after discography is completed in order to qualify the "flavor" of annular tear and whether or not that tear was leaking contrast material into the epidural space. *If it was discovered that you have a grade 4 or grade 5 leaking annular tear, then it is possible that the disc tested negative but truly was a pain generator. This is because if the disc leaks, it will not hold as much pressure and therefore the procedure will not be as irritative to the annular tear and the surrounding pain-carrying nerve fibers.

Many surgeons (and insurance companies) rely heavily on discography as an indicator of whether or not a fusion surgery for discogenic pain will be effective. Only the most experienced physicians should perform discography, for it is an art. There is also controversy about how much pressure should be utilized during the procedure. Many authorities say the disc should not be pressurized greater than 50 PSI; however, it is common practice for discographer to exceed 100 PSI looking for that painful disc.

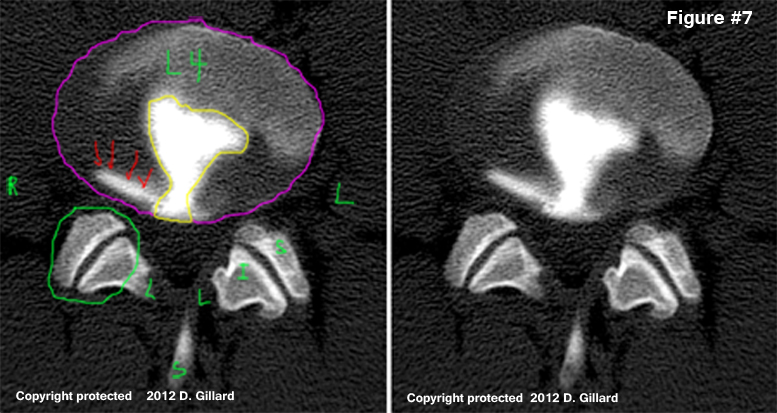

This is an overhead view (axial view) of an L4 disc that had just undergone discography. As noted above, follow-up CT scan should be completed if the discography testing was positive for concordant pain in order to elucidate the morphology of the annular tear and whether or not it was leaking.

Note the full thickness annular tear (a.k.a. radial annular tear) which has been outlined in yellow.

There is also a second type of annular tear: a circumferential annular tear, which the red arrows are pointing at.

As many of us predicted from the sheep studies of the 2000s, punching a hole in the disc with the needle (or a tear from rotational trauma for that matter [i.e., a rim lesion]), does not bode well for the future of that disc. More specifically, any puncturing or evening pricking through the substance of the animal disc will almost universally biomechanically doom that disc to a train of degenerative changes which may lead to a symptomatic disc herniation and all of its sequelae. [Rousseau MA, et al. Spine 2007; 32:17-24]

Eugene Carragee of Stanford has demonstrated confirmed hypothesis with humans! in an award-winning study which was published in Spine (Spine 2009; 34:2338-2345).

Specifically, in 2009 Carragee publish the results of the first long-term controlled clinical trial which followed patients for at least seven years following a needlestick injury to the disc, which occurred during provocative discography. Another group of people, who were specifically chosen to match the body morphology of the members of the experimental group, were followed for the same time. All participates in both study groups received a pre-MRI and a post MRI which was performed between 7 and 10 years after the beginning of the trial.

RESULTS: With regard to the lower 3 disc levels, the patients who had underwent discography 7-to-10 years prior had a significantly (P<0.05) more degenerative disc disease, new disc herniations (P=0.00003), Modic change development and degenerative disc disease development.

A LITTLE MORE TECHNICAL DESCRIPTION:

As we will learn in detail below, annular tears are not always seen on MRI, and never seen on x-ray. The best way to visualize annular tears is on CT Discography. A discogram is performed by injecting contract material into the center of the disc, and then watching to see if the dye leaks from that center along a radial tear. Figure #1 and #2 are examples of CT Discography. In Fig. #1 the injected dye (black) does not leak out of the nucleus. This is normal. Fig.#2 demonstrates a massive Grade 4 radial disc tear. Note how the contrast (black) has leaked out from the center of the disc through a massive complete radial tear. (See the Discography page for more information.)

The

other, less invasive way, to confirm the presents of an annular disc

tear is by MRI. High

Intensity Zones (HIZ)

are very effective at predicting the presents of a grade 4 radial annular

tear. Research agrees that HIZ (High Intensity Zone) is fairly accurate

at predicting the presents of an underlying annular tear. However a huge

debate still rages as to whether or not this HIZ sign is predictive

of that disc being a cause of the patients back pain.

The

other, less invasive way, to confirm the presents of an annular disc

tear is by MRI. High

Intensity Zones (HIZ)

are very effective at predicting the presents of a grade 4 radial annular

tear. Research agrees that HIZ (High Intensity Zone) is fairly accurate

at predicting the presents of an underlying annular tear. However a huge

debate still rages as to whether or not this HIZ sign is predictive

of that disc being a cause of the patients back pain.

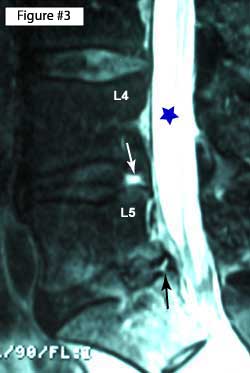

In Figure. # 3, My T2 weighted MRI is a prime example of an HIZ (white arrow). Note the bright white defect in the posterior part of the L4 disc, which is the same "intensity" (color) as the cerebrospinal fluid.

Also note another type of tear (black arrow) in the posterior part of the L5 disc which is not as hyperintense as the cerebrospinal fluid. Bogduk calls this type of annular tear a LIZ (Low Intensity Zone). it is thought to represent an annular tear that has healed or almost healed. There is no research on this.

To increase the chances of seeing a true annular tear on MRI, contrast (gadolinium) may be added. Researchers have noted that gadolinium will 'light-up' full thickness tears because the contrast will accumulate in the vascular granulation tissue with that tear (32). (read the whole story on HIZ Here.) HIZ are thought to represent a combination tear: the meeting of a full thickness radial tear with a concentric the annular tears.

Annular tears were first described by Schmorl and Hunghanns in 1932, but were more officially categorized by Hirsh and Schajowicz in 1952 and 1971(2) into the available flavors that we have today. Specifically, they described Concentric Tears as crescentic or oval cavities which were filled with fluid or mucoid material between lamellae of the annulus. These defects were a result of disruption of the short transverse fibers of the lamellae (these fibers hold the lamellae together), probably due to torsional forces (twisting) on the disc from repetitive twisting/turning movements or rotational type injury.

They also described Radial Tears as fissures extending from the surface of the annulus to the nucleus, as well as Transverse annular tears(aka: rim lesions) as tears in the very outer fibers of the annulus (Sharpey’s Fibers) near their insertion point at the ring apophysis (very outer portion of the bony vertebral endplate).

Since these initial descriptions, we have learned a lot more about annular tears, secondary to extensively studied both microscopically and macroscopically. Famed researcher Barrie Vernon-Roberts, who has devoted over 25 years of his career to the study of annular tears and disc degeneration, has published several papers on the subject in 1977, 1990, 1992, and final in 1997. To date, his 1992 paper entitled “Annular Tears & Disc Degeneration in the Lumbar Spine” contains one of the best descriptions of the three types of annular disc lesions yet written. I will use his research frequently through out this page. (3)

In a Volvo Award Winning paper, Roberts also laid to rest the erroneous theory that all three types of annular tears were interrelated(4), by demonstrating that a radial annular tear begins as a "cleft" from the nucleus and moves into the inner annulus. It next steadily progress outward until it finally makes its way into the outer periphery of the annulus fibrosus, which of course is infested with pain carrying nerve fiber. (5,6).

Now, let's talk a little more about each specific type of annular tear:

Radial Tears | Rim Lesions | Concentric Tears | HIZ Sign

References for this page:

1) Hirsch C, Schajowicz F, Acta Orthop Scand 1952;22:184-223

2) Schmorl G, Junghans H, “The human spine in health & disease”. New York: Grune & Stratton, 1971

3) Osti OL, Vernon-Roberts B, et al. “Annular Tears & Disc Degeneration” J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1992; 74-B:678-82

4) Kirkaldy-Willis WH, “The pathology & pathogenesis of low back pain. Managing Low back pain” New York, Churchill-Livingstone, 1983; pp 23-43

5) Osti OL, et al “Volvo Award- Anulus Tears & Intervertebral Disc Degeneration" – Spine 1990; 15(8):762-766

6) Vernon-Robert B, et al. “Pathogenesis of Tears of the Anulus”, - Spine 1997; 22(22):2641-46

30) Coppes NH, et al. “Innervation of anulus fibrosus in Low Back Pain.” Lancet 1990; 336:189-190

31) Freemont AJ, et al. “nerve in-growth into the diseased IVD in chronic back pain.” – Lancet 1997; 350:178-181

32) Ross JS, Modic MT, Masaryk TJ, AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990 Jan;154(1):159-62

© Copyright 2002 – 2016 by Dr. Douglas M. Gillard DC - All rights reserved